Brain Aneurysms - Multiple Ruptured

Woman survives catastrophic subarachnoid hemorrhage from Multiple Brain Aneurysms and continues to thrive 13 years later.

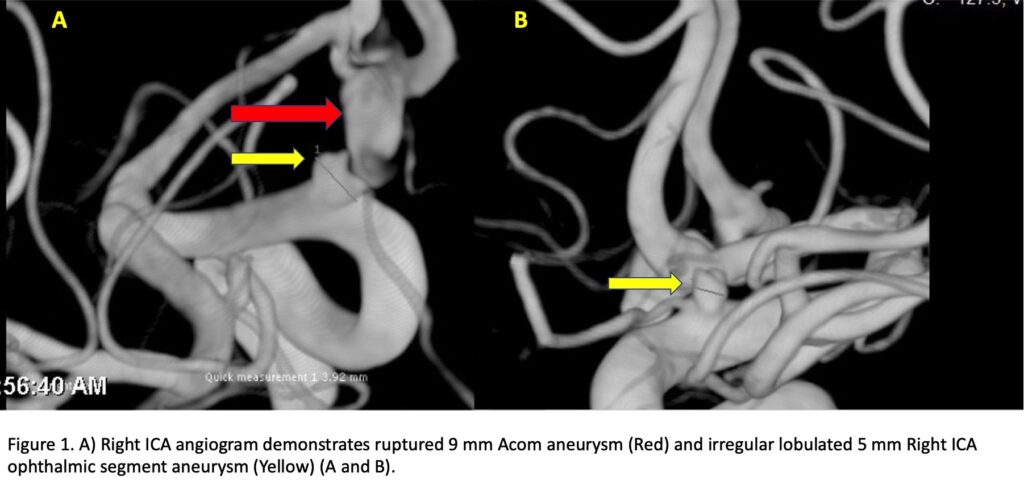

The patient is a 49-year-old woman who experienced the Worst Headache Of her Life (WHOL) and presented with poor grade Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (WFNS Grade 3-4) in late 2009. Catheter cerebral angiography confirmed multiple intracranial aneurysms, the largest measuring 9-10 mm and projecting inferiorly from the anterior communicating artery complex. A second 5 x 4 x 3 mm irregular lobulated aneurysm of the right ophthalmic ICA segment. (Figure 1)

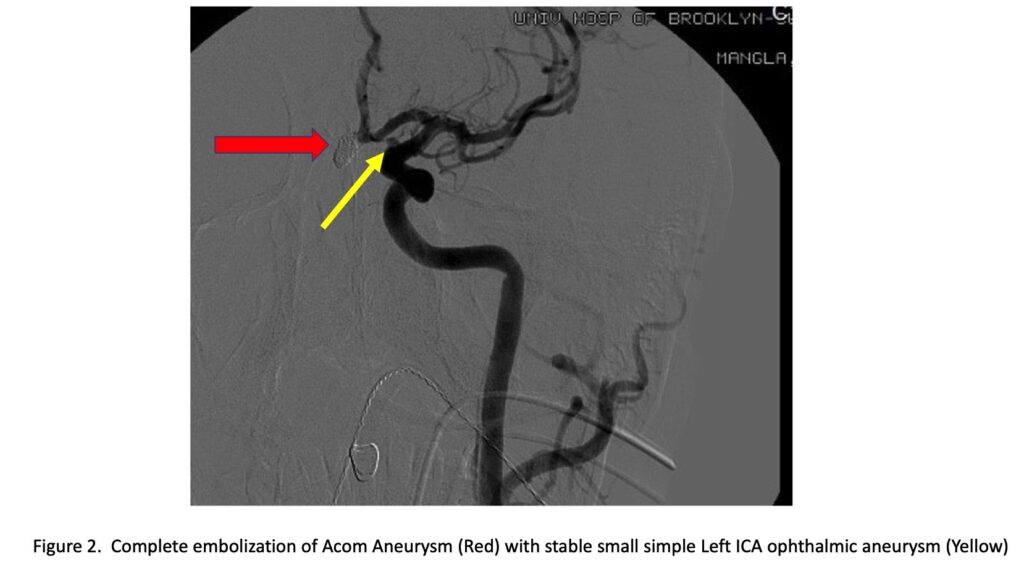

A third less than 3 mm smooth simple saccular aneurysm of the left ICA ophthalmic segment was also observed and felt to be unruptured and low risk. Based on the size, morphology, and pattern of hemorrhage; the anterior communicating artery aneurysm was thought to be the ruptured aneurysm was targeted for initial treatment and underwent primary coil embolization with complete obliteration after primary treatment and additional coil placements at 6 months for mild coil compaction. (Figure 2)

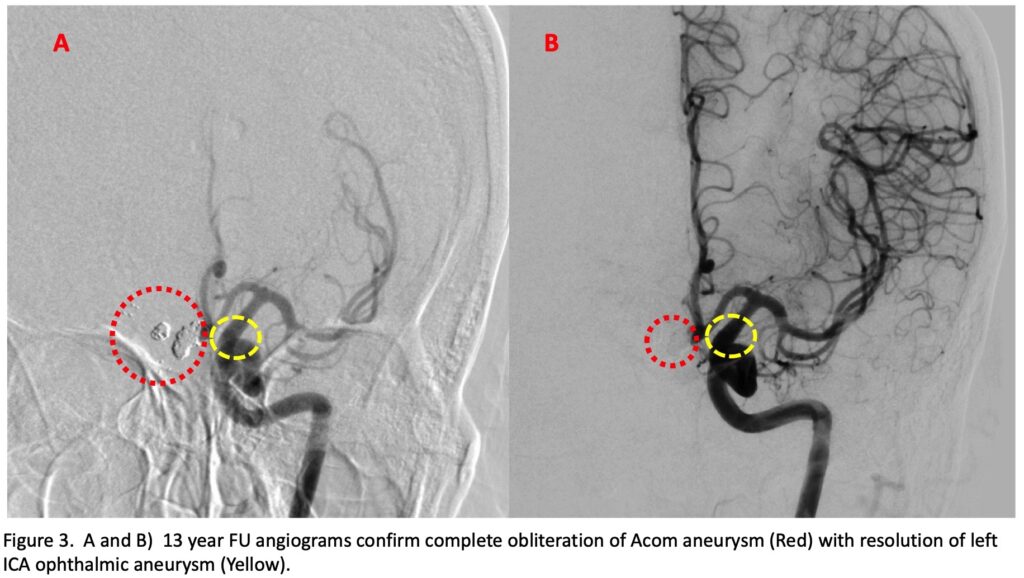

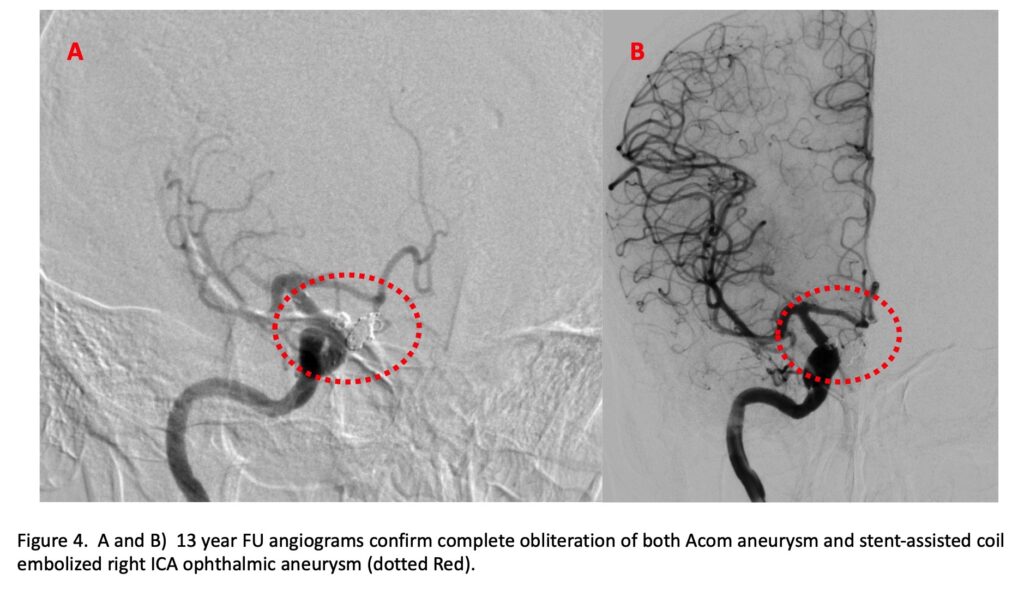

Based on the morphology (irregular, multilobular) and size of the right ICA ophthalmic segment aneurysm, the right ICA ophthalmic segment aneurysm was felt to be high-risk for future catastrophic subarachnoid hemorrhage and was treated in delayed manner after she recovered from her initial hemorrhage with stent-assisted coil embolization. After extensive critical care and clinical management, she made a complete clinical recovery from her initial brain hemorrhage gradually returning to all her Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and a modified Rankin Score (mRS) of 0. Clinical and angiographic follow-up thru the first 4 years continued to demonstrate stable angiographic obliteration of both treated aneurysms with absence of interval change of the smaller (<3 mm) left ICA ophthalmic segment aneurysm which we elected to continue to observe. She now presents for delayed clinical and angiographic followup in 2022 (13 years after her initial event), continuing to thrive functionally with only the occasional headache, but otherwise functionally intact, independent, and living a complete and normal life. Her current angiograms demonstrate stable complete embolization of both treated aneurysms, Anterior Communicating (Figure 3), and right ICA (Figure 4). In addition, the 3rd aneurysm of the left ICA ophthalmic segment is not well visualized, suggesting benign remodeling or at a minimum, absence of growth or progression.

Discussion:

The natural history of untreated ruptured brain aneurysms is very poor, with the classically quoted Finnish Study from the 1960’s of untreated ruptured intracranial aneurysms (RIAs) of 116 hospitalized patients reporting a 1-year mortality of 63%.[1] A more recent Study from Helsinki University Hospital reviewed their Aneurysm Registry of 6850 patients between 1968 and 2007, of which 510 patients were classified as untreated and stratified into generational epochs. “During a lifelong follow-up of 510 untreated SAH patients, the 1-year mortality rate was 65%, 5-year mortality 69%, and 10-year mortality 76%. Hospital-admitted poor-grade patients with untreated RIAs had 1-year mortality rates of ≈90%. The 1-year mortality rate was 75% for good-grade patients admitted within a week. In theory, today’s patients, who are admitted within a week after SAH and who are not in poor condition on admission, have an ≈25% possibility to survive a year if treated conservatively.”[2]

Early treatment of RIAs is highly recommended to prevent acute catastrophic rebleeding events. Landmark studies, specifically the prospectively randomized trial of 2143 patients, the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT), has demonstrated the short and long-term success of Endovascular Coiling in improving mortality rates and reducing the risks of rebleeding from the treated aneurysm. At 5 years, 11% (112 of 1046) of the patients in the endovascular group and 14% (144 of 1041) of the patients in the neurosurgical group had died (log-rank p=0.03), but the proportion of survivors at 5 years who were independent did not differ between the two groups: endovascular 83% (626 of 755) and neurosurgical 82% (584 of 713).[3]

In the same ISAT cohort followed up to 18.5 years from their initial ruptured event and treatment, 33 patients experienced a recurrent SAH event beyond 1 year, 17 patients from the treated aneurysm and 16 patients rebled from another source. The cumulative risk of a rebleed from the target aneurysm was .0216 and the incidence of recurrent SAH was one in 641 patient years for patients in the endovascular group. In the 16 patients that rebled from another source, 15 bled from another aneurysm (6 from a pre-existing aneurysm identified on the original angiogram, and 9 from a new aneurysm that was not present or reported).[4] The long-term durability and protection from rebleeding after endovascular treatment remains robust beyond 10 years, and the treatment and/or close serial observation of additional aneurysms should be strongly considered (as performed in our patient).

Interestingly, in this patient, her left ICA ophthalmic aneurysm was not seen on her delayed angiographic follow-up suggesting regression or disappearance. The natural history and evolution of cerebral aneurysms is a dynamic process which remains poorly understood and difficult to predict. There have been numerous isolated case reports and series of spontaneous regression, as we have seen in our patient, nevertheless, long-term serial imaging is generally favored, especially in patients with multiple brain aneurysms and a prior history of rupture.[5]

Conclusion:

Endovascular coiling has gained acceptance as a primary and durable approach to most ruptured brain aneurysms, however, a multi-disciplinary approach including surgical clipping, vasospasm prevention/therapy, hydrocephalous management, and advanced neurocritical care remain essential tools in the armamentarium of experienced neurovascular teams caring for these critically ill patients.

References:

[1] Pakarinen S. Incidence, aetiology, and prognosis of primary subarachnoid haemorrhage. A study based on 589 cases diagnosed in a defined urban population during a defined period. Acta Neurol Scand. 1967; 43(suppl 29):21–128.

[2] Korja M, Kivisaari R, Rezai Jahromi B, Lehto H. Natural History of Ruptured but Untreated Intracranial Aneurysms. Stroke. 2017 Apr;48(4):1081-1084. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015933. Epub 2017 Mar 1. PMID: 28250196.

[3] Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Birks J, Ramzi N, Yarnold J, Sneade M, Rischmiller J; ISAT Collaborators. Risk of recurrent subarachnoid haemorrhage, death, or dependence and standardised mortality ratios after clipping or coiling of an intracranial aneurysm in the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT): long-term follow-up. Lancet Neurol. 2009 May;8(5):427-33. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70080-8. Epub 2009 Mar 28. PMID: 19329361; PMCID: PMC2669592.

[4] Molyneux AJ, Birks J, Clarke A, Sneade M, Kerr RS. The durability of endovascular coiling versus neurosurgical clipping of ruptured cerebral aneurysms: 18 year follow-up of the UK cohort of the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) [published correction appears in Lancet. 2015 Mar 14;385(9972):946]. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):691-697. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60975-2

[5] Jayakumar PN, Ravishankar S, Balasubramaya KS, Chavan R, Goyal G. Disappearing saccular intracranial aneurysms: do they really disappear?. Interv Neuroradiol. 2007;13(3):247-254. doi:10.1177/159101990701300304